The Chrissertation

- Tanya Parker

- Nov 5, 2019

- 32 min read

Catchy title, I know.

Three years ago I graduated Uni. Fresh faced and with a skip in my step. I had aspirations to publish my dissertation, after being urged to consider it from my theory tutor. That never happened, partly down to being lazy, partly down to not knowing where to even begin. Disregarding that, I'm proud of my work. I never did well in any of the english subjects throughout school, so being told what I'd written was interesting or engaging enough to potentially be published had me over the moon.

So in lieu of that, I've posted it here below this page break:

The effect of MMO design on the creation and development of Social Structures within the game space and player base.

Introduction

This work intends to detail the design aspects of various ‘massively multiplayer online’ games, which hereby will be referred to as MMO’s, and how changes in approaches over the iterative development seen in the genre and wider industry has encouraged or hindered the creation of actual, or analogues to real life socio-economic classes, and the wider-scale ramifications thereof. Utilising Ray Oldenburg’s concept of ‘Third Places’, this text hopes to examine the social structures that have developed around the games chosen as case studies. The critical theories that will be applied are being utilised due to their relevance to the question or to the nature of the case studies as entertainment products and social spaces. Through the lens of critical theory, it is intended that this text will cover not only several viewpoints but also offer a more detailed discourse on the social nature of MMO’s.

The two case studies that have been selected for examination within the body of this text are the 2004 game ‘World of Warcraft’ by Activision Blizzard, and the 2003 game ‘EVE: Online’ by CCP Games. These two works were chosen due to their nature as contemporaries of each other, having been released to the public at similar times, in addition to their relationship with each other. It is felt that these two games are sufficiently different that by comparing these two games, their approaches to the social aspects of their works, the communities that have grown around them, and how the design ethos of the two works differ a framework can be built to explore how malleable the recreational aspect of the genre can be. Whilst the use of two case studies may be seen as quite limiting, an argument could be made that given the stark differences between the two case studies, any other works chosen would either have been made irrelevant, or just seen as a less radical version of one of the two polarising case studies.

The concept of a digital world running parallel to the Real world, with its own social systems, rules, political movements and even histories was a common idea even before the arrival of Ultima Online in 1997. It could be argued that Ultima Online was the first MMO game to accrue a large consistent audience. In a 2015 article on Rock Paper Shotgun, writer Jake Tucker conducted an interview with long-term player and community leader,‘Petra Fyde.’ At the time of writing, Ultima Online had been running in one form or another for the past eighteen years, successfully supporting a high enough population to continue hosting of the game and support services. In the interview, Petra gives her reasoning to Ultima’s continuing support as:

“[Ultima] endures because it is diverse, appealing to many different people with many different play types and makes no demands… ...you do what you want, when you want, if you want… ...It endures because players have ‘ownership’ of property, they have houses which they have built and furnished, they ‘live’ in UO. There’s a sense of presence here.”

(Tucker, 2015)

At least for Ultima Online, its continued success lies in the player-driven worlds and narratives. Castronova mentions within Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games, it is mentioned that;

‘the ancestors of MMORPGs were text-based multi user domains. (MUDs)’

(Castronova, 2005)

Taking this into account, the logical progression from text-based and player driven action would have been a system not too dissimilar from Ultima Online. MMO development was small and sparse in the years following, partly due to the costs associated with the genre, such as development and infrastructure.

Chronologically, the next stand out success in the genre is that of Blizzard’s World of Warcraft, hereafter referred to within this text as WoW . Announced in 2001 then released in 2005, WoW built on the developments presented by forerunners such as the 3D graphics system made popular by Everquest. WoW grew into a colossal game, with a peak of 12 million players in 2010. WoW Arguably became the genre codifier for several concepts, mechanics and ideas among the playerbase and game designers alike. Many following MMO’s tried to ape WoW’s success and scope, with few coming close. In a 2015 article, Alan Bradley wrote for GamesRadar;

‘Though many have tried, none have yet succeeded in toppling the king. World of Warcraft continues to succeed in large part because Blizzard is never content to rest on their (cash padded) laurels.’

(Bradley, 2015)

To compare WoW and Ultima Online’s business models, focuses and strategies, an interesting dissonance is made apparent. Ultima focused on player-driven action and engagements early on, and ran with it for the following eighteen years. WoW built on what preceded it, and attempted to immerse the player in a series of storylines, placing the player in the epicentre of the action. Whilst both paths have proved to a certain extent successful, ostensibly it could be shown that through its larger size and greater financial worth, WoW is a much more successful game.

As MMO’s are a uniquely modern phenomenon, it can be argued that there is a level of cross-pollination from other disciplines and schools of thought. To this, Louis Sullivan’s statement of ‘Form follows Function.’ would suggest that the main focus point for an MMO game, regardless of its genre or setting will be the fact that it will have a need to incorporate social activity on several levels, due to their nature as a space for massive numbers of people. This point is also raised by Quandt and Kröger in ‘Multiplayer: the Social Aspects of Digital Gaming.’ Within the text they state that

‘Online games can be understood as a form of ‘social media,’ creating new socio-culturally and politically relevant spaces for interaction.’

(Quandt, Kroger,2013)

This acknowledgement that online, fictional spaces have a cultural and political element to them could be extrapolated out further, which raises the question asked by this text. To recognise that these digital spaces have a relevance, even to themselves, they need to have worth to the player. Mechanically this is easily justified through the fact that at the core of the work, it is a product of entertainment. However, as suggested by Quandt and Kröger, the nature of an MMO requires it to be looked at as a social space. This they address through the referencing of

‘social capital, which assumes that a system of self regulating social associations and closely connected interpersonal networks generates trust, commitment and participation.’

(Quandt, Kröger, 2014)

Through this lens of social capital, the simples interactions between players, ranging from friendly conversation to multi-user, in game social groups and guilds become more than what they appear to be, and are in fact a subconscious cataloging of players, much in the same way that a user of a social network prunes and grows their network of friends, contacts, followers and acquaintances.

As a starting point this text will briefly cover a possible reason as to why the player feels compelled to continue playing their avatar within the context of the game, through a lens of critical theory. The meta-stories that these players often dream up and design based on their avatars, their actions and the impact impart worth and value on the digital puppet of their character. An argument could be made that this impartation of ‘meta worth’ upon the character also imparts a desire to see it not harmed or diminished. Within the essay ‘The Myth of Sisyphus,’ the work of french philosopher Albert Camus, he dealt with the philosophical reasonings behind committing suicide. Whilst a strong comparison, the idea of ceasing activity within the game space, and removing the character, albeit temporarily from the game space has at least thematic connections with a person ending their own life. Camus likens life itself to the mythic task of the grecian mythological character Sisyphus. Camus uses the myth to illustrate his exploration of the relationship between his concept of the ‘Absurd’ and suicide. Camus describes the absurd as being

‘[the] divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting.’

(Camus, 1942)

within the confines of an MMO, an argument can be made that both the relationship between both the player and their avatar, and between the avatar itself and the game world. Camus equates the absurd to breaks in the monotony of day to day life, the brief moments of existentialism many people feel on occasion. Within the text he write

‘Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday and Saturday according to the same rhythm —this path is easily followed most of the time. But one day the "why" arises and everything begins in that weariness tinged with amazement.’

(Camus, 1942)

It is entirely possible that similar moments occur during play. MMO mechanics can often be repetitive and grinding, a feature acknowledged by Frank Pearce, World of Warcraft’s Executive producer in a 2006 interview for Spiegel Online international. Pearce states:

‘There are certain features that people would describe as a grind, and we're aware of these features. Aside from the fact that it's time consuming, at the end of the day some of that stuff -- it's just not fun.’

(Pearce, 2006)

The acknowledgement of elements of the game being unenjoyable, which may lead to players realising the ‘absurdity’ of their actions within the game space, culminating in them ceasing play and effectively committing Avatar suicide by removing themselves from effecting the game space further.

World of Warcraft

Continuing with World of Warcraft, whilst the game is not the progenitor of the mechanic, the player-created ‘Guild’ is a staple of WoW’s social structure. Serving a similar function to their middle age namesakes, WoW’s guilds are primarily used as spaces where like minded individuals can group up and pursue similar goals, regardless of whether that’s excelling at player vs player combat, progressing through the storyline, or successfully completing a large multi-person dungeon. Whilst not a requirement for playing the game, joining a guild offers numerous benefits to the player, such as growing their social capital through the connections they will make, allowing for easier fiscal gain through pooled guild resources. Whilst the players guild does not affect the game narratively, the player-coordinated services offered by them can help the player experience the game in a much more fluid sense, and through this the guild has an indirect influence on the narrative experienced by the player. The guild as a social venue exists in a form similar to Ray Oldenburg’s concept of a ‘third place.’ First suggested in his book, ‘The Great Good Place’ Oldenburg breaks down the three places thusly:

‘Daily life, in order to be relaxed and fulfilling, must find its balance in three realms of experience. One is domestic, a second is gainful or productive, and the third is inclusively sociable, offering both the basis of community and the celebration of it.’

(Oldenburg,1991)

Within ‘Multiplayer: the Social Aspects of Digital Gaming.’ Thorsten and Kröger use oldenburg’s model to look at the entirety of a multiplayer game as a third place, but a case can be made for the guild as a social structure existing as a recreational space within the recreational space of the game itself. The guild functions in a separate way entirely to the aspects of WoW that closest match with living and work spaces. ‘Professions’ (Fig.1) have been a key aspect of playing WoW since its launch in 2004, this strongly suggests a synergy with the ideals of the ‘second place’ of the workspace. the three-space model was completed with the release of WoW’s fifth expansion pack, ‘Warlords of Draenor’ released in 2014. For an article in the guardian, Keith Stuart writes that

‘Players will also be able to build and upgrade their own garrisons.’

(Stuart, 2014)

Within the game world of WoW, Garrisons act as a private space which the player can customise to their own specifications. This private, enclosed area ties in to Oldenburg’s idea of the first place, which is living space. If the player-built garrison is the first place, and the areas wherein they pursue their characters progression, or to expand the argument, even the places wherein they engage with the core mechanics of the game are the second place. It stands to reason that the player co-ordinated social groupings of the guild is a close idea to Oldenburg’s concept of the third place.

However, due to developments in WoW’s greater design ethos, the integrity of the guild in the social space of the game has been undermined to some extent. From WoW’s official website, via the internet wayback machine, guilds are mentioned to incidentally offer the service that;

’...players in good guilds can go places and do things that players in poor guilds or no guild can't. This is especially the case at maximum character level, where the dungeons become very challenging.’

(Blizzard, 2008)

The guild acting as a service for the player, allowing for greater co-ordination and therefore a greater success when player groups attempt the more difficult end game content. However, relatively newer changes and additions to the game experience may have eroded that purpose of the Guild. WoW’s 2009 Patch 3.3.0 added the ‘Dungeon Finder’ From the patch notes, it is described as thus;

‘This feature connects all realms… ...using an advanced matchmaking system, making it easier for players of all levels to find a dungeon group.‘

(Blizzard, 2009)

Whilst the dungeon finder was initially not designed to facilitate easier impromptu access to the difficult endgame content of the game, when compared to having to organise access through a guild or through application of the individual players social capital. However the train of thought that led to the introduction of the dungeon finder progressed to the end game ‘raid’ content with the introduction of the Raid Finder in patch 4.3.0 in 2011. The patch notes describe the Raid finder as being a

‘grouping feature [that] allows players to quickly and easily form a pick-up raid for… ... endgame content.’ (Blizzard, 2011)

The design focus for this addition being clearly focused on allowing for greater accessibility to the end game experience. It could be argued that for every player that will have used the raid finder to co-ordinate a raid experience, the guild as an abstract service will have lost users, and over time an argument could be made that this service will erode the presence of the guild as a third place within context of the game.

Whilst this point will be discussed in greater detail later on in the text, it is felt that a special mention needs to go to the game WoW, in the context of how the business model of the product, from the get go affects the playerbase in a broad, generally social position. Whereas other games in the genre are experimenting with their business model, and how it ties into the content they deliver, WoW has, for the most part been unshaken in their mandatory subscription-based model. As mentioned in a 2004 article for Gamespy, Rainier Van Autrijve makes it clear that the, at that point unreleased game would require a $12.99-14.99 subscription fee in order to continue play. This ‘paywall’ bars access to the content of the game to those who either lack the disposable income to play, or any of a multitude of possible reasons to not purchase a month of game time. Whilst in theory limiting the access to the game to a point, this then means that the game development team have no impetus to further throttle the game content.

This gated community aspect to the game exists in a physical manifestation as well. Fig 2. is taken from a NeoGAF thread, which discussed games with incredible draw distances. Fig 2. is an screenshot of the area of the WoW space named ‘The Eastern Kingdoms’ with the draw distance of the game upped to levels not normally attainable. Through this screenshot, the peculiarly crafted geography of WoW is made clear. Though Blizzard’s drive to provide as much variety in content as possible has objectively succeeded, an argument could be made that it came at a cost. Fig 2 clearly shows the stark divisions within the space, with natural barriers such as rivers and mountain ranges being used to ridiculous extents, breaking apart the cohesive look of the world, and further demarcating individual, standalone areas.

Another point based in the economic systems in WoW expanding from the discussion of the gated entry inferred by the subscription model. The existence of this monetary payment to access content, and to ultimately gain the benefits of this third place. The example of WoW as a curated experience which requires the participant to pay for entry has a strong equivalent within the physical world in that of the Amusement Park. Within the text of ‘The Global Theme Park Industry’ by Salvador Clavé, an Amusement Park is defined as being an environment

‘[that] is meticulously designed to handle visitors so that they are entertained and, especially, so that they spend money in an orderly, safe, relaxed atmosphere.’

(Clavé, 2007)

This definition can be applied broadly to the approach taken by Blizzard in regards to the development and creation of WoW. Compared to other games in the genre, WoW can be thought of as a safe experience. Whilst hostile player interactions are possible, there is a specific demarcation between the realms where these interactions can take place, referred to as PVP worlds, with realms disallowing these interactions outside of further demarcated and hard to reach locations within the game space referred to as PVP. A third, ‘secondary’ realm type exists wherein players are encouraged to explore their own narrative ideals alongside the pre existing narrative of the game space itself. These secondary realms are referred to as RP PVE, or RP PVP respectively. Fig 3. is a chart depicting the ratios of these realm types. The data for this chart was taken from the WoW Realm Status page, listing each WoW Realm, its type, population, physical location and if the realm is experiencing issues or not. The Realm Status page could be found at ‘eu.battle.net/wow/en/status’ as of 29th of november 2015.

From this visualisation, a distinction can be made that of the 266 public realms available, 54% of those realms allow for the players to freely fight amongst themselves, adding an element of risk to the game. However this risk element is flawed, and ties into the definition of an amusement park offered by Clavé. Whilst the space inside these realms is not ‘safe’ in the sense that a particular player can be preyed on and attacked by fellow inhabitants of the game space, the game mechanics have stripped away the risk element of this outside of finding yourself in a different area and losing a relatively small amount of time within the game space. The penalties for the player dying within the world space, be it at the hand of a computer controlled dire wolf, or at the hand of another player character is equally minor. From WoWWiki, their ‘newbie guide,’ an article designed to orientate new players and expedite their exploration of the game states the following penalty for dying within the game space;

‘Upon dying in World of Warcraft, all of your equipped items immediately take a 10% durability reduction’ (WoWiki, 2015)

This reduction of the risk associated with failure to little more than an abstracted fine, given that the reduction in item durability can be removed through interacting with NPC vendors and repairing the damage taken means that the player is divorced from the feeling of loss.

To lead on from the physical economics, and amusement park nature of the experience, an important aspect of the social landscape of WoW is the exploitation of both people, and the game mechanics to provide, outside of the game, an in-game currency black market. Whilst a simple metric for gauging the size of this market, searching for ‘WoW Gold Selling’ at the time of writing returns over four million results, as shown in Fig.4 . Clearly, this aspect of the game is a well-documented phenomenon. In Games of Empire, by Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter, the issue of gold selling was discussed at length. Within the text they make mention that

‘While an MMO’s initial programming— code manufactured and owned by a corporate publisher— sets the constituted parameters for virtual existence, it is the constitutive bottom-up behavior of player populations, the interaction of thousands of avatars, that gives this form content.’

(Dyer-Witheford, De Peuter 2009)

If a portion of the player base of the game is willing to ‘splash out’ as it were and illegitimately purchase gold in quantities enough to allow a both a business and arguably a culture to spring up around this aspect of the game. For a 2015 article for Eurogamer.net, Robert Purchese recounts;

‘In 2005 I found myself at a gold shop, breathlessly confirming my intention to buy 1000 World of Warcraft gold for £100… ...And it got easier each time I went back. I ended up spending hundreds. I didn't talk about it in the game - only to friends on chat programs, voice or text, hosted outside of WOW. I knew it was against the rules and that I could be banned, and that I could lose everything I'd played for’

(Purchese, 2015)

The act of skipping the ‘grind’ of mechanics as referred to earlier in the text through this illicit and outside of the agreed-upon game rules is described with language commonly associated with addiction. The referring to the act becoming easier every time they went through with it, and the aversion to talking openly about the topic are noteworthy to say the least. The ‘Stanford Marshmallow Experiment’ by Walter Mischel dealt with the phenomenon of delayed versus instant gratification. It could be argued that a player facing a choice between putting time, effort, luck and a comparatively smaller amount of capital versus an instantaneous reward by going through the third party gold selling route.

The text ‘Cognitive and Attentional Mechanism in Delay of Gratification,’ penned by Walter Mischel, Ebbe Ebbesen and Antonette Raskoff Zeiss in volume 21 of the ‘Journal of Personality and Social Psychology’ states that;

‘This choice is influenced mainly by the subject's expectations concerning the probable consequences of his choice. These consequences include the relative subjective values of the immediate and delayed outcomes themselves as well as other probable reinforcing outcomes associated with each alternative.’

(Ebbesen, Mischel & Zeiss, 1972)

This can be used to lend context to the habits recounted by Purchese in regards to the purchasing of WoW gold. His lack of willingness to discuss the act within the communication channels built into WoW could be seen as either a conscious choice to avoid bringing attention to the fact that he’s broken the terms of use of the game. As publically stated on the WoW website:

‘Blizzard owns, has licensed, or otherwise has rights to all of the content that appears in the Game. You agree that you have no right or title in or to any such content, including without limitation the virtual goods or currency appearing or originating in the Game’

(Blizzard,2015)

This section of the Terms of use clearly places Purchese in breach of agreement, and barring him access to the service is entirely valid. This can be seen as a reinforceable outcome to dissuade a player from taking the quicker route, which can be also seen as a shrewd business decision. Incentivising the delayed gratification means that a typical player would theoretically spend more time logged into the game, which will be compounded over time, with players maybe becoming enamoured with a goal, and spending a longer period of time playing the game than they would have done otherwise. With a monthly payment system in place, a slow ‘grinding’ experience may have been pushed in order to extract a greater amount of capital from a player. However, as mentioned by Purchese later in the article, WoW has undertaken measures to curb the growth and success of these third parties, on March 2nd, 2015 Blizzard announced the launch of ‘WoW Tokens’ These tokens can be bought from an in-game real money marketplace, and sold on the in-game auction house for an amount set by the seller. Fig 5. is an excerpt from the WoW Website further detailing the mechanics of WoW Tokens.

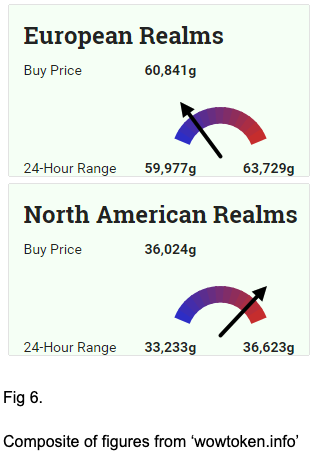

To look at this from a social point, the implementation of the WoW token legitimizes the notion of buying gold, as unlike through the channels discussed by Purchese, the WoW token is a service offered by the game itself. Not only does this ostensibly feed the money back into the game, but the success of the scheme depends on the player base engaging in it. As the token is sold extensively on the in-game auction house, its in game worth depends entirely on what people are willing to pay for it. From the third-party tracking website ‘wowtoken.info’ the following information was garnered:

the two portions of Fig 6. detail the average selling price of WoW Tokens across the US and European servers, realm being an interchangeable term for the instance of the game being run on a particular server. From these two statistics, a conclusion about the acceptance of the WoW token could possibly be drawn. Using the concept of Supply and Demand, as explained in Microeconomics by Besanko and Braeutigam. Of the four rules of supply and demand as detailed in their work the most relevant to this point is the first rule and is posited as such:

‘Increase in demand + unchanged demand curve = higher equilibrium price and larger equilibrium quantity.’

(Besanko,Braeutigam 2010)

This rule can be used to explain the discrepancy between token worth across the US and European realms. The higher value on the European side may be down to less of the playerbase being tempted to purchase the token to resell, with a comparatively larger base of players willing to purchase the token from a fellow player using ‘gold,’ the natural currency of the game. An argument could also be made that the European realms players are more focused on the risk versus reward aspect to earning gold within the game.

To conclude direct examination of WoW, the points raised will be cross referenced against each other. The construct of the guild as discussed firmly exists as a third place within the social and physical spaces of the game, necessitated by the game mechanics being compared to a first-space labour element. However, moves made to lower the laborious elements such as the raid finder erode the importance of the guild as a whole, as it means that without the labour element that so strongly embodies the first place, the relevances of the guild as a structure begins to fall away. This measure of removing the labour element is carried over with the introduction of WoW tokens, and could also be seen as a facilitator of the decline in importance of player-driven guilds. Whilst the raid finder removes tedium by randomly grouping willing players to do high-level content faster, compared to having to organise and engage with other players through a guild, the WoW Token instead relies on the player having the economic capital to not only support the monthly subscription, and the added cost of the Token itself. Whilst the token removes the labour element by giving the purchaser a high value item, the item in and of itself only has a worth within the game because the players allow it to, which shows a differing level of involvement between the two approaches to the problem of the labour element. The introduction of the WoW token also has the added benefit of effectively re-privatising the black market of gold selling, which whilst is at the whim of the economic demand of the relevant game server does not have the associated risks such as account loss or hijacking. The two approaches differ through the involvement of the wider community. The introduction of the Raid Finder directly undercut the player-driven and created guilds, whilst the value and worth of an individual token varies depending on not only which side of the EU/US server divide, but also the economic status of the individual servers, which is an aspect the player base can directly change.

EVE: Online

Having concluded the discussion of WoW, next this text will examine the work ‘EVE: Online’ by Icelandic developer CCP Games. For a 2005 article in Gamasutra, Nathan Richardsson, the then senior producer on the game gave the following quote about the game and its inspirations:

‘The sci-fi feel and vastness of space from Elite and the social interaction of massively multiplayer and player vs. player gaming from Ultima Online…. …We feel that the emotions involved with losing something of value is just as important as gaining something of value, it makes a very immersive experience. There have to be lows to make the highs more enjoyable. PvP allows us to achieve that.’

(Rossignol, 2005)

Having already looked into the social spaces of WoW, and how hands-on the development team are with managing the game experience, an argument can be made that EVE stood out from the crowd through its embracement of Ultima style player-driven narratives and through its unusual focus on potentially-devastating player versus player combat, hereafter referred to as PvP. This divide between EVE and its contemporaries is discussed by Richardsson further on in the article;

‘Our strong belief in PvP and a single universe is probably the main differentiator between us and other MMOs. We strongly believe that MMOs should focus on social interaction between people, but many MMOs tend to go in the opposite direction.’

(Rossignol, 2005)

the notion that the developers themselves consider their work a stand out lends it credence in relation to being studied in this context. To continue the study of EVE: Online, an examination of the Oldenburgian places available to the player needs to take place. The narrative world of EVE has a distinctly business-orientated flavour to it. Whereas WoW’s player-made and player-driven groups are given the name of ‘Guilds’ the social equivalent of the guild in EVE is that of the Corporation. Already from this stage, just through careful use of language the game is blending the business and labour first place with the recreational third place. Outside of the naming, EVE corporations and WoW Guilds have much in common, from the 2007 book ‘Second Life Herald: The Virtual Tabloid That Witnessed the Dawn of the Metaverse’ by Peter Ludlow and Mark Wallace they make mention that;

‘In MMOs such as Lineage and EVE Online, Guild-like groups can band together and go to war against each other for control over valuable resources, or simply for bragging rights’

(Ludlow, Wallace 2007).

This is doubly true for EVE. Through the game systems and CCP’s lax pruning of the system, a complicated and in-depth economy has developed. In a 2007 article for Gamasutra, Leigh Alexander explored the first of CCP’s ‘Quarterly Economic Newsletters’ The notion of a multiplayer space having such an organised and in-depth economic system that the developers feel the need to issue quarterly economic reports. Something to note is the mention of the report being prepared by a qualified economist, Dr. Eyjolfur Gudmundsson. Within the article, Gudmundsson is quoted as saying;

‘In fact, with more than 200,000 players, the economic system of EVE is becoming so vast and complex that it is possible for the virtual world of EVE and the real world to learn from each other.’

(Alexander, 2007)

To quickly compare, If the nature of WoW’s third place is that of a well-maintained system not unlike a garden, CCP’s focus on a well-functioning economic system and a gameplay structure where real losses can occur,to compound that with the remarks of Dr. Gudmundsson, EVE’s ‘vast and complex’ economy entwined around the game mechanics present tints the third place nature of the game with a rather overt feeling of a business-associated First place.

The strength of corporations within eve, and the curious meta game that has developed around them is best explored through an article about an EVE player ‘Samahiel Sotken’ Sotken has found himself in the interesting position of his main purpose within EVE society as being a diplomat for a large player-created and driven alliance called the ‘Goonswarm’, named as such due to its origins as being formed by players from the third party internet community ‘Something Awful’ which refers to its users as ‘Goons.’ Within the article, the writer Steve Messner mentions;

‘He [Sotken] illustrates the way that EVE has evolved from beyond the confines of its installation folder on your hard drive—no longer a game but a virtual society where people like Samahiel contribute in ways that often transcend the mechanics of EVE entirely. While most interaction in the galaxy of New Eden is as tangible as a torpedo slamming into your hull, Samahiel’s currency is far more subtle. Samahiel deals in control.’

(Messner, 2015)

The rest of the article consists of an interview with Sotken, detailing his role as a diplomat for the ‘Goonswarm’ Sotken himself contributes more to his corporation during his time outside of the game world than from within, through the creation and dispersal of Propaganda related to the in-game universe that has built up. This curious blending of spaces, wherein a player can act as an integral member of day-to-day happenings within a game without even realising their avatar in the virtual space is a level of immersion only really attained by EVE Online. The use of the word ‘contribution’ infers something is being used, inferring something separated from leisure. The contribution of time and labour suits a workplace more than that of a recreational space, which reinforces the prior point of EVE’s recreational nature being incredibly business focused.

Sotken’s influence both inside and outside of the game space is best examined through the prior referenced idea of Social Capital. A point can be raised that the lax nature of CCP, and their focus on letting the players have much creater control over their characters within the ongoing development of the player-created narrative compared to the more rigid and structured gameplay and narrative space of WoW has led to a greater value placed social capital compared to the electronic currencies of ISK and Gold in EVE and WoW respectively. From the Rock Paper Shotgun article on Sotken and his contemporaries, Sotken is quoted as saying

‘The easiest way to motivate someone is letting them buy into a narrative… ...People want to belong to something bigger than themselves that fulfills their values, that enables them to do something they didn’t think they could do normally.’

(Messner, 2015)

Sotken’s out-of-game exploits in selling a fictionalised and exaggerated narrative of the ‘real’ events occurring in the game space. The use of language such as ‘Narrative’s and the mention of players wanting to belong to something bigger, suggests that the player base in general maintain a strong connection to the created narrative of the game. This could suggest that the player base sees the narrative as being more of a recreational collaborative aspect of the game, when compared to the labour-driven mechanics.

The curious level of dedication that EVE players have to the game can possibly be traced back to the development model and design ethos of developer, CCP Games. A curious addition to the mechanical structures of EVE is the concept of player avatar skills incrementing in real time. From the official ‘Evelopedia’ entry for Skill training, the mechanics behind this base of character advancement is detailed as:

“EVE has a unique approach to pilot advancement. Your account has the ability to train one or more pilots at a time no matter whether you're online or not. If you start a training a skill before you go to sleep, it will continue its advancement in real time while you are sleeping. Keep in mind that only one pilot can be training one skill at a time.”

(CCP, 2015)

This feature allows for a measure of ‘idle’ play, where the equivalents of the grinding, tedious incrementation of player skills and abilities can be progressed without player interaction outside of the player initialising and queuing up the skills to be gained. This removes the labour element from gameplay entirely, meaning the player has more time to spend playing the aspects of the game they enjoy. This may explain how players such as Sotken are able to rationalise spending significant amounts of time engaged with the meta-societies of the game whilst being outside of the virtual game space, as a method of further utilising the idle time that the mechanics of the game facilitates.

An aspect of the ‘physicality’ of the EVE universe compared to that of WoW that has yet to be discussed is the division of the playerbase through the server structure. Whereas the ‘universe’ of WoW is built up from 247 ‘realms’ (Not sure if a citation’s needed for this, but it got lifted from the Blizzard Website) the structure of the playable space in EVE is instead split between only two servers, named Shards. Even then, the division between the two shards is only there out of apparent necessity. One shard is named Serenity, and houses the player space for the Chinese market, with Tranquility supporting the rest of the world. (CCP, 2015) This ties into CCP’s design ethos. From the prior-mentioned interview for Gamasutra, Nathan Richardsson discusses these design choices;

“We fully understand the reason behind sharding, instancing and the PvE focus... ...We however decided to take the more difficult path and try to take on those obstacles head-on... ...We're complex, we're open ended, we're fully PvP oriented and you can lose six months work in a second.”

(Rossignol, 2005)

This further begins to distance EVE through its design ethos from its contemporaries. The fact that CCP have stuck to this model since the creation of the game, through a decade of advancements and changes to the ‘landscape’ of the genre is a testament to their design ethos, especially in consideration of the sheer difference exhibited between EVE and the colossally successful WoW. The fact that the space the game world inhabits is singular, and not the same version repeated over numerous servers may be why the players of EVE regard the game space with such seriousness. The singular instance of the game world, coupled with the fact that the game actively punishes mistakes through the legitimization of loss means that anyone investing time and labour into the game is aware of the fact that though involving themselves within both the game space and the other players inhabiting the space, they risk losing the results of their work not only from the random circumstances of the game, but also the whims of the other players present. This sets up a system where social capital, and the connections you have to the other players of the game are just as important as the more traditional measures of strength in MMO’s, such as the monetary capital and the ‘force’ capital of the players.

Whilst the concept of a secondary monetary currency existing within the game space that is funded and inherits value from the physical world currency used to purchase it has already been discussed through the WoW Token, an argument can be made that EVE, being the progenitor of the concept through their PLEX system, introduced in 2008, and replacing the pre-existing EVE Time Code system in 2014. The PLEX system fills the same niche as the WoW token, as a way to curb the growth and existence of third-party illicit real-money trading. In a 2008 Dev Blog titled ‘Real Money Trading is bad, mkay?’ CCP Game Master ‘Grimmi’ detailed the situation the EVE game space was facing in regards to the actions and ramifications of third party traders, and the risks it posed to the game experience;

‘There are also the macro miners and mission runners, complex farmers and assorted rabble of this sort that causes general nuisance and keeps the regular players from being able to enjoy EVE as they would like. Price of minerals, ore, ice, implants and so on is driven down by this kind of activity and thus ways for normal players to make ISK are effectively ruined’

(Grimmi, 2008)

The mentioning of the trickle-down effect that these traders had in an interesting lens to look at the issue through. This is compounded by the fact that the design ethos behind the economic model used in EVE has been described by EVE’s in house economist Dr. Eyjolfur Gudmundsson within a later Developer post detailed a change to the game that resulted from observations he’d made of the economy. Titled ‘Shuttles No Longer sold by NPC’s’, the devlog detailed the removal of a service offered by non-player organisation, and how it had a knock on effect on the economic system of the game as a whole. From the article, Dr. Gudmundsson writes that;

‘Previously shuttles were available in every station at a fixed price of 9000 ISK per unit, this allowed pilots to purchase shuttles at a low price and great convenience. There was a side effect to this though – an artificial price cap of 3.6 ISK per unit of tritanium’

(Gudmundsson, 2008)

The removal of a faked system where the game itself offers a service, with the effect of capping the worth of a minable and refinable material, with the rationale that the player-run portion of the game space will be able to expand and fill that niche is detailed further as being;

‘This change is also along the lines of our general philosophy of the design of markets in EVE, that all items should be player produced and based on the incentive to make a profit from providing the item to other players.’

(Gudmundsson, 2008)

The mentioning of this aspect of their design philosophy, coupled with the risk of loss, and the incentivisation of time outside of the game space further legitimises the game space as a real and ‘living’ experience.

An alternate explanation for the ‘dedication’ that players have for EVE when compared to players of other multiplayer games can possibly be found in an earlier raised point, that of Albert Camus’ interpretation of the Myth of Sisyphus. Whilst the ‘End Game’ of WoW entails players experiencing the same content numerous times in order to collect various armour sets in order to be on the same level of use as their contemporaries, to which is an easy comparison to the titular myth from antiquity. However in contrast to that EVE online’s end game content is more nebulous and less defined. The official EVE Wikipedia presents the following statement:

‘Unlike other MMOs, Eve does not present you with a specific goal when you begin playing such as reaching a 'level cap' or 'reaching the end game' etc. It is up to you to decide what your personal driving force is in Eve.’

(CCP, 2015)

This lack of an endgame forced on the playerbase synergises well with the PvP focus of EVE. The comparisons to Camus’ text however still apply to EVE. As mentioned in the beginning of the text, Camus uses the myth of sisyphus as a vehicle to explain his concept of the ‘Absurd’ He then goes on to explore the options a person has when confronted with the absurd, and suggests that;

‘The absurd man says yes and his efforts will henceforth be unceasing If there is a personal fate, there is no higher destiny, or at least there is, but one which he concludes is inevitable and despicable. For the rest, he knows himself to be the master of his days.’ (Camus, 1942)

This rejection of the absurd, and the personal assurance and creation of goals can be compared to EVE in such a way that a player may make the conscious realisation that to engage in other games that are driven and controlled by the developer is to trap themselves in an unending and ultimately purposeless system, and instead spending their leisure time within the third space of EVE Online, and making an impact, no matter how negligible upon the player-run environment of the game.

To conclude this chapter on EVE: Online, a summary and cross examination of the points is in order. Richardsson’s earlier statements regarding CCP Games approach to the development of EVE being a strong differentiator between them and their contemporaries compounded by the starkly different feel of EVE compared to other large scale MMO’s, and the comparatively alien approach to involvement within the game space. The immersive power, and scope of the experience CCP have nurtured and developed over the years EVE Online has been open to the public can be shown through the actions and ramifications players have on the space. Individual players such as Sotken have been able to carve a niche in entirely player-created social spaces in such a way that they are able to contribute to the space without interacting with it first hand, and also through the cumulative habits of the total player base such as the findings of Dr. Gudmundsson, where his observations of the patterns in the player-created market led to the removal of provided features due to the knock-on effect it had on prices of goods in the virtual space. This hands off, adaptable design ethos has helped foster an atmosphere within the space of EVE that has created a space quite unlike its contemporaries.

Conclusion

To bring this text to a close, the two case studies will now be directly compared with each other, and conclusions to the points raised will be given. Firstly to reiterate Richardsson’s point from above and initially earlier in the text, CCP games make explicit mention to their development practices and design ethos as being distinct from that of their contemporaries, which in this instance is irrefutably WoW, given their similar launch dates and scale of their operations. This dissonance between the two studios, and their approaches to community management. With WoW being comparable to an Amusement Park experience, EVE Online’s expansive hands-off experience can be likened to a more realistic experience, through the greater options available to the player. Another point that acts as grounding for this assertion of EVE being a ‘truer’ experience than WoW is that comparing the two, EVE has a capability for the player to bear true loss of time and labour, through the permanence of death and failure, compared to the comparatively light game- monetary fine of WoW. An argument can be made that this increased realism within EVE gives power to the Social Groups that have grown up around the experience, whereas nothing quite to the scale of the EVE corporations have arisen in the WoW game space. Within EVE, the fear of loss could drive players to join such organisations, through the reassurance of the group offering a ‘safety net’ as seen in a differing context through CCP removing a non-player shuttle service, and allowing the private sector that is the player base to step in and replace that service, as mentioned by Gudmundsson. This addition of player agency to offer services to other players is a stark contrast to the precautions built into the mechanics of WoW itself. The lack of player-run agencies within the WoW space could also be down to the point raised early in the text, that of the increased pushing of in-house alternatives to the social institution of the Guild. With players needing to socialise with other players within the WoW space more and more, it is no surprise that the social aspect of the game is stunted in comparison to EVE Online’s. To finalise, this text intended to offer an insight into the MMO genre, and through the examination of two polar opposite studies, showcase the breadth of approaches fielded by developers to handle the emergent social spaces within their works.

Bibliography

Bradley, A. (2012) Best MMORPGs | GamesRadar at: http://www.gamesradar.com/best-mmorpg/ (Accesed on 20.10.15)

Sullivan, L. (1896) The tall office building artistically considered [online] At: https://archive.org/details/tallofficebuildi00sull (Accessed on 15.10.15)

Quandt, Thorsten and Kröger, Sonja (2014) Multiplayer: the social aspects of digital gaming (Thorsten Quandt, Sonja Kröger) Oxford: Routledge

Tucker, J. (2015) 18 Years Later, Why Are People Still Playing Ultima Online? (2015) At: http://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2015/06/30/ultima-online-retrospective/ (accessed on 18.10.15)

Castronova, E. (2005) Synthetic Worlds : The Business and Culture of Online Games Chicago: University of Chicago press

Statista. (2005) WoW Subscription number 2015 | Statistic At: http://www.statista.com/statistics/276601/number-of-world-of-warcraft-subscribers-by-quarter/ (Accessed on 19.10.15)

Wallace, M (2005) The Game is Virtual. The Profit is Real. -The New York Times At: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/29/business/yourmoney/the-game-is-virtual-the-profit-is-real.html?_r=0 (Accessed on 20.10.15)

Stuart, K (2013) World of Warcraft: warlods of Draenor expansion announced | Technology | The Guardian At: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/08/world-of-warcraft-warlords-of-draenor (Accessed on 23.10.15)

Oldenburg, R (1999) The Great Good Place Boston: Da Capo Press

Blizzard, Via Internet Archive. (2008) WoW -> Info -> Basics -> Joining Guilds At: http://web.archive.org/web/20080216005409/http://www.worldofwarcraft.com/info/basics/joiningguilds.html (Accessed on 24.10.15)

Van Autrijve, R. (2004) Gamespy: World of Warcraft Launch Date Announced - Page 1 At: http://pc.gamespy.com/pc/world-of-warcraft/563565p1.html (Accessed on: 26.10.15)

Spiegel Online. (2006) Real-Time Gaming: An Interview with the maker of ‘World of Warcraft’ - SPIEGEL ONLINE At: http://www.spiegel.de/international/real-time-gaming-an-interview-with-the-maker-of-world-of-warcraft-a-433643.html (Accessed on: 28.10.15)

Dyer-Witheford, Nick, and de Peuter, Greig. (2009) Games of Empire : Global Capitalism and Video Games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Purchese, R. (2015) World of Warcraft and the battle against black market gold · Eurogamer.net At: http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2015-04-29-world-of-warcraft-and-the-battle-against-black-market-gold (accessed on: 30.10.15)

Mischel, W, Ebbesen, E and Zeiss A. (1972) ‘Cognitive and Attentional Mechanisms in Delay of Gratification’ in: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 21(2) pp.217

Blizzard Entertainment. (2015) Blizzard Entertainment: World of Warcraft Terms of Use At:

http://us.blizzard.com/en-us/company/legal/wow_tou.html (Accessed: 31.10.15)

Blizzard Entertainment. (2015) Introducing the WoW Token At: http://eu.battle.net/wow/en/blog/18141101/introducing-the-wow-token-3-2-2015 (Accessed 3.11.15)

WoWToken (2015) WoW Token Info At: https://wowtoken.info/ (Accessed 3.11.15)

Besanko, D and Braeutigam, R. (2011) Microeconomics, 4th ed. New York City: John Wiley & Sons.

Rossignol, J. (2005) Gamasutra - Interview: Evolution and Risk: CCP on the freedoms of EVE Online. At: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/2411/interview_evolution_and_risk_ccp_.php (accessed: 9.11.15)

Ludlow, P and Wallace, M (2007) The Second Life Herald: The Virtual Tabloid that Witnessed the Dawn of the Metaverse. Cambridge: The MIT Press

Alexander, L (2007) Gamasutra - EVE Online Releases Economics Newsletter, Reveals Demographics. At: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/107200/EVE_Online_Releases_Economic_Newsletter_Reveals_Demographics.php (accessed 10.11.15)

Messner, S (2015) Meet the Players Making EVE Online Propaganda. At: http://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2015/10/01/eve-online-propaganda/ (Accessed 12.11.15)

EVElopedia (2015) Skill Training - EVElopedia. At: https://wiki.eveonline.com/en/wiki/Skill_training (accessed 16.11.15)

Blizzard Entertaiment (2015) Realm Status - Community - World of Warcraft. At: http://eu.battle.net/wow/en/status (Accessed: 19.11.15)

CCP Spitfire (2014) The ETC is Dead, Long Live the PLEX Activation Code. At: http://community.eveonline.com/news/dev-blogs/the-etc-is-dead-long-live-the-plex-activation-code/ (Accessed: 21.11.15)

EVElopedia (2015) Shard - EVElopedia. At: https://wiki.eveonline.com/en/wiki/Shard (Accessed 19.11.15)

CCP Grimmi (2008) Real Money Trading is bad, mkay? At: http://community.eveonline.com/news/dev-blogs/real-money-trading-is-bad-mkay/ (Accessed 21.11.15)

CCP Dr.EyjoG (2008) Shuttles no longer sold by NPCs. At: http://community.eveonline.com/news/dev-blogs/shuttles-no-longer-sold-by-npcs/(Accessed 21.11.15)

Crawford,G, Gosling V and Light, B. (2013) Gamers: The Social and Cultural Significance of Online Games. Oxford: Routledge

Camus, A (1955) The Myth of Sisyphus. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Clavé A, (2007) The Global Theme Park Industry. Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 2007.

Ludography

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004) World of Warcraft [Download] PC. Irvine: Blizzard Entertainment

CCP Games. (2003) EVE Online [Download] PC. Reykjavík: CCP Games

list of illustrations

Figure 1. World of Warcraft Professions (2015) [Web Image] At: http://us.battle.net/wow/en/profession/ (Accessed on: 24.10.15)

Figure 2. World of Warcraft Zones Screenshot (2015) [Web Image] At: http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=1029976&page=5 (Accessed on: 6.12.15)

Figure 3: Parker, C. (2015) World of Warcraft Server Breakdown [Web Image] In possession of: The author: Online.

Figure 4: Google Search Result (2015) [Web Image] At: https://www.google.co.uk/#q=wow+gold+selling (Accessed on: 30.10.15)

Figure 5: World of Warcraft Token (2015) [Web Image] At: http://us.battle.net/wow/en/blog/18141101/introducing-the-wow-token-3-2-2015 (Accessed on: 3.11.15)

Figure 6: WoW Token Composite (2015) [Web Image] At: https://wowtoken.info/(Accessed on: 3.11.15)

Appendix

Comments